Math 918, Spring 2026: F-Singularities

Course Documents

Here are the two general references for the course.- Linquan Ma & Thomas Polstra's F-Singularities: A Commutative Algebra Approach; called [MP] in the daily update.

- Alessio Caminata & Alessandro de Stefani's Notes for course on F-singularities; called [CdS] in the daily update.

- An additional resource is Karl Schwede & Karen Smith's Singularities defined by the Frobenius map; however note that this book requires more knowledge of algebraic geometry than is covered by the prereqs of this course, so I will not be explicitly suggesting it as complementary reading (even though their order of topics matches ours most closely!).

Office Hours: Mon 1:30-2:30 and Thurs 12:30-1:30. Or stop by my office when my door is open.

Homeworks

- Homework 1: [PDF] and [TeX] + [math-hw.sty] (style file needed to compile!)

- Due on Friday Feb 6th at midnight. Submit on Gradescope.

- [Solution] to HW1.

- Homework 2: [PDF] and [TeX] + [math-hw.sty] (style file needed to compile! same as last week)

- Due on Friday Feb 20th at midnight. Submit on Gradescope.

- Homework 3: [PDF] and [TeX] + [math-hw.sty] (style file needed to compile! same as last week)

- Due on Friday March 6th at midnight. Submit on Gradescope.

In-Class Handouts

- 02/03 Worksheet: [Fedder's Criterion]

- 02/05 Cheatsheet: [Macaulay2 Cheatsheet]

HCC Info

You have access to the Holland Computing Center (HCC) for this class! To use these resources, you will need an account associated with HCC that is separate from your University of Nebraska account and credentials:

- If you need an HCC account: https://hcc.unl.edu/new-user-request and request the math918 group.

- If you already have an HCC account from a prior class or research, you can add the class group to your account or move your account to the math918 group: https://hcc.unl.edu/group-addchange-request.

Note: Not actually required to add/change group! ANY access to HCC is good enough for us. But you're still welcome to join the class group if you e.g. want to keep class access separate from research access for some reason.

**You will need to activate your DUO two factor for your HCC account in order to use the resources. Without this you will not have access! This is different from the TrueYou DUO you use to log into other UNL services.**

Here is some other important info:

- For more useful links and notes for students taking a class using HCC resources, please see https://hcc.unl.edu/docs/faq/class_students.

- While using HCC resources for this class, be aware of HCC's class account guidelines and center's policies: https://hcc.unl.edu/hcc-policies.

- Pay special attention to the guidelines for class accounts since data is removed at the end of the semester: https://hcc.unl.edu/hcc-policies#class-groups

Daily Update

Use this table of contents list to jump to a specific day. Info for future classes is a tentative plan, and will be updated by the day after the class with what actually happened.

- Jan 13

- Basics & Notation: Day 1

- Jan 15

- Basics & Notation: Day 2

- Jan 20

- Completions and Proof of Kunz's theorem

- Jan 22

- Finishing proof of Kunz's theorem + starting F-splitting

- Jan 27

- Proof that F-splitting can equivalently be checked for some/any $e$; examples (including $F$-finite regular local rings); the statement of Fedder's criterion; viewing $\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ as a rank 1 free module for regular $S$.

- Jan 29

- A HW correction; fact about the generating $\Phi$ and ideal containments; more general statement of Fedder's criterion.

- Feb 03

- $F$-splitting localizes; the $F$-split locus is open; the completion of Fedder.

- Feb 05

- We learned some M2 basics (everything needed to do Fedder's criterion) and also learned how the HCC works.

- Feb 10

- Defined (eventual) splitting along elements and SFR. Proved that local + SFR implies domain, and that F-finite regular local rings are SFR.

- Feb 12

- Fedder examples; proof that if $R$ is SFR then so is $R_{\mf p}$.

- Feb 17

- Proof that if $R_{\mf p}$ is SFR for all $\mf p$, then $R$ is SFR; proved that all $F$-finite regular rings are SFR; stated that for SFR rings all module-finite extensions split and started proof.

- Upcoming

- Finishing up Ch 3 of [MP]: finishing the above proof; doing the "test element" criterion that reduces checking SFR-ness to checking eventual $F$-splitting along a single (well-chosen) $c$.

Jan 13

Big Assumptions (for all semester!): p = a prime number; q = a power of p; all rings are unital, commutative, and noetherian. For a very long time (up until reduction to char p), all rings are characteristic p.

We covered the beginning of Ch 1 of [CdS], up through and including Remark 1.8. (See also very first section of [MP].) Useful fact: In a reduced (char p) ring, when p-th roots exist, they are unique!

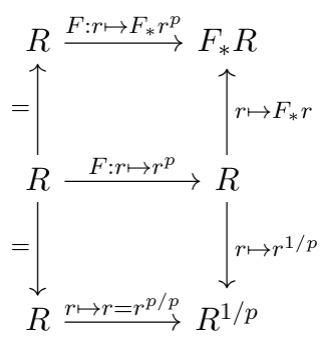

We also concretely looked at $R^{1/p}$ and $F_*R$ in the concrete example where $R=\mathbb F_2[x]$, and saw how these are generated (as $R$-modules) by $\{1,\sqrt x\}$ and $\{1,F_*x\}$, respectively. We saw more generally that when $R= \mathbb F_p[x_1,\ldots, x_n]$, that $F_*R$ is generated by $\{F_*(x_1^{a_1}\cdots x_d^{a_d})\: | \: 0\leq a_i \lt p\}$. We even saw that this generating set is actually a basis! Finally, the following commutative diagram showed us that all three perspectives are really "the same" map. Note that all vertical maps are isomorphisms/equalities, the horizontal maps are all different ways of writing the Frobenius, and the whole bottom row only makes sense when $R$ is reduced.

Jan 15

Defined a separable polynomial and a perfect field (Ref: Section 15.5 of Eloísa's Math 818 notes). In particular, a char $p$ field is perfect if and only if $F$ is a surjection. $K=\mathbb F_p(T)$ is a non-perfect field example. We stated #5 below as a bonus problem (but originally stated it wrong! I meant to say $R^p$ not $R^{1/p}$, my apologies).

We then worked for a while on questions #1-4, and went over the answers to #1-3:

- Describe the $R$-module structure of $F_*R$ when $R=\mathbb F_p[x,y]/\langle xy\rangle$.

Generators are $\{F_*x^i, F_*y^i\: | \: 0\le i \lt p\}$. I.e., the same as for the polynomial ring, but we remove all the ones corresponding to the cross terms that are already zero in this quotient ring.

Relations are $yF_*x^i = 0$ and $xF_*y^i=0$.

- Describe the $R$-module structure of $F_*R$ when $R=\mathbb F_2[x^2,x^3]\subset \mathbb F_2[x]$.

Generators are $\{F_*1, F_*x^2, F_*x^3, F_*x^5\}$. Notice that the monomials in $R$ are every power of $x$ EXCEPT for $x$ itself. So via taking $x^aF_*x^b = F_*x^{2a+b}$ for $b\in \{0,2,3,5\}$, we see that even just $F_*x^{2a+2}$ and $F_*x^{2a+3}$ cover all possible powers $\ge 6$. The only other seemingly missing monomial is $F_*x^4$, but $F_*x^4 = x^2F_*1$.

Relations are $\begin{aligned} x^3F_*1 &= x^2 F_*x^2 & x^3F_*x^3 &= x^2F_*x^5 \\ x^4F_*1 &= x^3F_*x^2 & x^4F_*x^3 &= x^3F_*x^5\end{aligned}$.

- Describe the $R$-module structure of $F_*R$ when $R=\mathbb F_3[x,y]/\langle y^2-x^3-x\rangle$.

Generators are $\{F_*1,F_*x,F_*y\}$. Clearly the 9 monomials $\{F_*x^iy^j\: | \: 0\le i,j\lt 3\}$ would suffice as a generating set, so now we'll show that the other 6 of them are actually redundant via taking multiples of our defining equation. As we go down the list, we will only use higher up monomials to get the lower ones.

- $F_*y^2 = xF_*1 + F_*x$ (via original equation)

- $F_*xy = yF_*1 - xF_*y$ (via $\cdot y$)

- $F_*xy^2 = yF_*y - xF_*y^2$ (via $\cdot y^2$)

- $F_*x^2 = F_*xy^2 - xF_*x$ (via $\cdot x$)

- $F_*x^2y^2 = xF_*x^2 + xF_*1$ (via $\cdot x^2$)

- $F_*x^2y = yF_*x - xF_*xy$ (via $\cdot xy$)

There are no relations!

- Describe the $R$-module structure of $F_*R$ when $R=\mathbb F_p(T)[x]$.

Generators are $\{F_*(T^jx^i)\: | \: 0\le i,j\lt p\}$. No relations!

Notice that $TF_*x^i = F_*(T^px^i)$. So if we had only used the generators from the perfect field case, we would be missing being able to write an element like $F_*T$. Or said another way, previously in the perfect case we knew that if we wanted to write $F_*(ax)$, we could always pull out the $a$ via taking a $p$-th root, so that $F_*(ax) = a^{1/p}F_*x$. But if the Frobenius isn't surjective, we can't do that anymore!

- Give an example of a ring $R$ where $R^{p}$ is NOT isomorphic to $F_*R$. In other words, an example where the inclusion $R^p\hookrightarrow R$ is NOT the same map as the Frobenius. [Corrected typo from earlier statement: I wanted $R^p$ not $R^{1/p}$!]

We then noticed a pattern: drawing the corresponding varieties for the two ``free'' examples gave us affine space (the polynomial ring) and a smooth elliptic curve (#3). Drawing the two ``non-free'' examples gave us two lines crossing (#1) and a cuspidal cubic (#2).

Definition: The ring $(R,\mathfrak m, k)$ is a regular local ring if $\dim R = \dim_k \mathfrak m /\mathfrak m^2$. In other words, if the Krull dimension = the embedding dimension.

A ring $R$ is a regular ring if $R_{\mathfrak m}$ is a regular local ring for every maximal ideal $\mathfrak m$.

You will eventually learn a lot more about regular rings in Math 906.

Kunz's Theorem: $R$ is regular if and only if the Frobenius is flat.

Definition: $R$ is $F$-finite if $F_*R$ is a finitely generated $R$-module.

For a local ring and a finitely generated module $M$, you already know that $M$ is flat if and only if it is free. This and our new definition give us an immediate corollary to Kunz.

Corollary: Let $(R,\mathfrak m)$ be an $F$-finite local ring. Then $R$ is regular if and only if $F_*R$ is free.

Jan 20

Some facts (that became exercises):

-

Prove that $F$ induces an isomorphism on Spec.

The induced map on Spec takes a prime ideal $Q$ to $F^{-1}(Q)$. If $r\in Q$, then $r^p=F(r)\in Q$ and thus $r\in F^{-1}(Q)$. Conversely, if $r\in F^{-1}(Q)$ this means $r^p\in Q$, but $Q$ is prime so $r\in Q$.

- Prove that $F_*^e$ is an exact functor. (In particular, we first saw what it does to maps and to modules: just throws an $F_*^e$ decoration in front!)

See proof of Prop 1.10(1) in [CdS].

- If $W\subset R$ is a multiplicative set, then $W^{-1}(F_*^eR)\to F_*^e(W^{-1}R)$ via $\frac{F_*^e r}{w}\mapsto F_*^e(\frac{r}{w^{p^e}})$ is a $W^{-1}R$-module isomorphism.

See proof of Prop 1.10(2) in [CdS].

Definition: A sequence $(r_n)_{n\in \mathbb N}$in $R^{\mathbb N}$ is Cauchy in the $I$-adic topology if for all $t\in \mathbb N$ there exists a $d\in \mathbb N$ such that for $n,m\geq d$, we have $r_n-r_m\in I^t$. Let $C_I(R)$ be the set of Cauchy sequences. Let $C^0_I(R)$ be the sequences convernging to zero, i.e., s.t. for all $n$ there exists $m$ s.t. for all $i\geq m$, $r_i\in I^n$.

Facts/Definition: $C_I(R)$ is a ring and $C^0_I(R)$ is an ideal; the completion is $\widehat R^I = C_I/C_I^0$. We're going to only use this for local rings and the $I=\mathfrak m$ case, written just plain $\widehat R$, which satisfies:

- $\widehat R$ is a local commutative unital noetherian ring

- Completion at $\mathfrak m$ is faithfully flat

- $R$ is regular if and only if $\widehat R$ is regular.

- (Cohen Structure Theorem, equicharacteristic case) Suppose $(R,\mathfrak m,k)$ is a complete local ring containing a field. Then $R\cong k[[ x_1,\ldots, x_n]]/I$. Further, $R$ is regular if and only if $R\cong k[[x_1,\ldots, x_d]]$.

Proof of Kunz's theorem (regular implies flat):

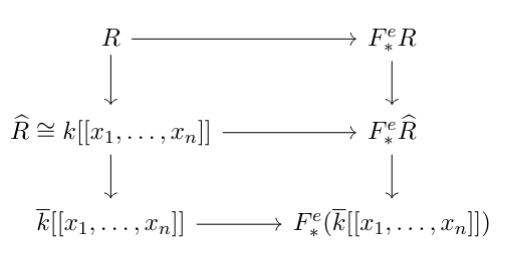

$R$ is regular iff $R_Q$ is regular for all $Q$; and a map $\phi$ is flat iff $\phi_Q$ is flat for all $Q$. Further, $F_*^e$ commutes with localization. Thus we reduce to the local case. Now consider

Recall fact: In such a diagram (where both vertical maps are faithfully flat), if the bottom map is flat then so is the top one. So sufficient to show for the complete case, and likewise sufficient to do for a power series ring over an algebraically closed field, but we (basically) already did that! ■

We started the proof of the other direction (in the style of [CdS]) but didn't finish; however we did get through the following:

Definition: Let $(R,\mathfrak m)$ local. Then $x_1,\ldots, x_n$ is Lech independent if having $a_1x_1+\cdots + a_nx_n=0$ for $a_i\in R$ in fact implies that $a_i \in \langle x_1,\ldots, x_n\rangle$ for all $i$.

Equivalently: letting $\mathfrak q = \langle \underline x\rangle$, they are Lech independent iff they minimally generate $\mathfrak q$ and $\mathfrak q/\mathfrak q^2$ is a free $R/\mathfrak q$-module.

Lech's Lemma: Let $(R,\mathfrak m)$ be a local ring and $x_1,\ldots, x_n$ be Lech independent elements which generate an $\mathfrak m$-primary ideal. If $x_1=y_1z_1$ then \[\ell_R(R/\langle x_1,\ldots, x_n\rangle)=\ell_R(R/\langle y_1,\ldots, x_n\rangle) + \ell_R(R/\langle z_1,\ldots, x_n\rangle)\]

Proof in Lemma 2.6 of [CdS]

Jan 22

Proposition: If $\underline x\in R$ is Lech independent and $\varphi:R\to S$ is a flat map, then $\varphi(x_1),\ldots, \varphi(x_n)$ is Lech independent in $S$.

Proof: Let $I=\underline x$. Then by Lech independence, $I/I^2 \cong (R/I)^n$ as $(R/I)$ and as $R$-modules. But then flatness gives \[ (IS)/(IS)^2 \cong (S/IS)^n \] and by rank reasons clearly $\varphi(\underline x)$ is still a minimal generating set. ■

Proposition: If $\underline x$ is Lech independent and $x_1=y_1z_1$ then $y_1,\ldots, x_2,\ldots, x_n$ is L.i.

Proof: From last time, we saw that $\underline x : y_1 = \langle z_1,x_2,\ldots, x_n\rangle$. So suppose we have coefficients $a_1z_1 + \sum_{i=2}^n a_ix_i=0$. Multiply by $y_1$ to get $a_1(y_1z_1)+\sum_i (a_iy_1)x_i=0$. By Lech independence of $\underline x$, this means $a_1 \in \underline x \subset \langle z_1,x_2,\ldots, x_n\rangle$. Further, means $a_i \in \underline x:y_1 = \langle z_1,x_2,\ldots, x_n\rangle$ as desired. ■

Proof of Kunz's theorem (flat => regular): $R$ is regular if and only if $\widehat R$ is regular, and by the same diagram before, if $F_*\widehat R$ is a flat $\widehat R$ module then $F_*R$ is a flat $R$-module. (In fact, this is iff because $\widehat R\to \widehat{F_*R}$ is canonically $\widehat R\to F_* \widehat R$.) So WLOG $R$ is complete local ring, and $R\cong k[[x_1,\ldots, x_n]]/I$. Let $S=k[[x_1,\ldots, x_n]]$.

We can further WLOG assume $n =$ embedding dimension (recall that = $\dim_k\mathfrak m / \mathfrak m^2$ = by NAK the minimal number of generators of $\mathfrak m$), since if not just throw away redundant $x$'s. Thus $\underline x$ is Lech independent, and so is $\underline x^{[q]}$, and then also so is $x_1^{a_1},\ldots, x_n^{a_n}$ for combo of powers.. On the one hand, by Lech's length lemma, a base case of $\ell(R/\mathfrak m)=1$, and induction, we get that $\ell_R(R/\langle x_1^{a_1},\ldots, x_n^{a_n}) = \prod_i a_i$. But we also can do the same thing to $S$ and see that $\ell_S(S/\langle x_1^{a_1},\ldots, x_n^{a_n}) = \prod_i a_i$.

Thus $S/\langle \underline x\rangle^{[p^e]}\to S/(I+\langle \underline x\rangle^{[p^e]}\cong R/\mathfrak m^{[p^e]}$ is an isomorphism for all $t$, and so $I\subset \underline x^{[q]}$ and by Krull's intersection, $I=0$. ■

Now... new topic! Moving onto Frobenius splitting. We defined $F$-splitting, saw a proposition about how it relates to other split maps, and saw two examples.

Definition: $R$ is $F$-split if there exists some $R$-module map $\pi\in \operatorname{Hom}_R(F_*R,R)$ such that $\pi\circ F = \operatorname{id}_R$.

Equivalently: There exists an $R$-module map $\pi:F_*R\to R$ such that $\pi(F_*1)=1$.

We saw that was the same since being a splitting exactly means that for all $r\in R$ we have $r = \pi\circ F(r) = \pi(F_*r^{p})=\pi(rF_*1)=r\pi(F_*1)$.

Proposition: If $R$ is $F$-split then $R$ is reduced.

Proof: Let $\pi:F_*R\to R$ be our splitting. If $\pi\circ F=\operatorname{id}_R$, this forces the first map to be injective. And we saw $F$ injective iff $R$ reduced. ■

Example: If $R=k[x]$ or $k[[x]]$ then $R$ is $F$-split. We saw that in fact these examples are both free, with $R$-basis of $\{F_*x^i\: | \: 0\le i \lt p\}$. By freeness, we can define a map by doing whatever we want on the generators, such as the standard monomial splitting, which sends \[F_*1\mapsto 1, \qquad F_*x^i\mapsto 0\ \ \forall 0\lt i\lt p.\]

Proposition: Suppose $\varphi:R\to S$ is split (as an $R$-module map). If $S$ is $F$-split then so is $R$.

Proof: Suppose that $\varphi$ is split via $\gamma:S\to R$, and that $F_S$ is split via $\pi:F_*S\to S$. Then $\gamma\circ\pi\circ (F_*\varphi)$ is our desired splitting of $F_R$. See this via \[\gamma\circ\pi\circ (F_*\varphi)(F_*1) = \gamma\circ \pi(F_*\varphi(1)) = \gamma(\pi(F_*1))=\gamma(1)=1.\quad ■\]

Example: Let $G$ be a finite group such that $p\not|\,|G|$. Let $R$ be a char $p$ ring with a $G$ action, and let \[R^G = \{r\in R \: | \: g\cdot r = r \ \forall g\in G\}\] be the invariant subring. The inclusion $R^G\to R$ is always split via the Reynold's operator: \[R\to R^g\qquad r\mapsto \frac{1}{|G|}\sum_{g\in G}g\cdot r\] Thus whenever $R$ is $F$-split, the invariant ring $R^G$ is also $F$-split.

As a more specific example, take $G=S_3$ and $R=\mathbb F_p[x_1,x_2,x_3]$. Have $G$ act on $R$ via $\sigma\cdot f(x_1,x_2,x_3) = f(x_{\sigma(1)},x_{\sigma(2)},x_{\sigma(3)})$. Examples of polynomials in $R^G$ are $x_1x_2x_3$ and $x_1+x_2+x_3$, but NOT plain old $x_1$ or plain old $x_1x_2$. Using the previous polynomial example and the above invariant example, we see that if $p\ge 5$ then $R^{S_3}$ is $F$-split.

Today's class prompted some good requests for examples, which I will give you on Tuesday:

- What's an example of a reduced ring that is NOT $F$-split?

- What's an example of an invariant ring that is $F$-split even though $p||G|$?

Finally, an in-class exercise was to prove the following, which we will go over on Tuesday:

Proposition: The following are equivalent for a char $p$ ring $R$.

- $R$ is $F$-split.

- There exists some $e\gt 0$ such that $F^e:R\to F_*^eR$ splits.

- For all $e\gt 0$ the map $F^e:R\to F_*^eR$ splits.

Jan 27

Proof of proposition from last week (F-split iff for some e iff for all e): 1 implies 3: If $\pi:F_*R\to R$ is our splitting, then notice that $\pi\circ F_*\pi \circ \cdots \circ F_*^{e-1}\pi:F_*^eR\to R$ is a splitting! Notation $\pi^{\star e} =$ such a composition, and in fact $\psi\star \phi := \psi\circ F_*^e\phi$.

3 implies 2: clear

2 implies 1: let $\pi:F_*^eR\to R$ be our splitting. Then \[ R \stackrel{F}{\to} F_*R \stackrel{F_*F^{e-1}}{\to} F_*^eR \stackrel{\pi}{\to} R \] so take $\pi \circ F_*F^{e-1}$ as our splitting. ■

(Non)Example: The ring $\mathbb F_2[x^2,x^3]$ is reduced, but is NOT $F$-split. (Proved in HW 1 #4).

Example: Here are some invariant rings that ARE $F$-split even though $p$ divides the order of the group (so that the Reynold's operator proof won't work):

- If $G$ acts via the trivial action, then for ANY ring $R$ we have $R^G=R$. So regardless of the group order, if $R$ is $F$-split then clearly so is $R^G$.

- If $G=S_2$ and $R=\mathbb F_2[x,y]$ and we do the same symmetric group action of permutating the variables from last time. Then $R^G = \mathbb F_2[x+y,xy]\cong \mathbb F_2[w,z]$ which is regular and thus $F$-split.

The following theorem was an in-class exercise.

Theorem: Any $F$-finite regular local ring is $F$-split. Any complete regular local ring is $F$-split.

By the Cohen structure theorem, if $R$ is a complete regular local ring then $R\cong k[[x_1,\ldots, x_d]]$ where $k$ is the residue field. From seeing this example before we know that $F_*R$ is free (though possibly infinitely generated if $k$ is a bad field!), that $F_*1$ is part of a basis, and so the standard monomial splitting works. Recall the standard monomial splitting sends $F_*1\mapsto 1$ and $F_*(\lambda_i x^{\alpha})\mapsto 0$ for all the other generators. ■

By Kunz, regular means $F_*R$ is flat. Since we're further $F$-finite and local, $F_*R$ is free. So as long as we can prove that $F_*1$ is part of a minimal generating set (i.e., part of a basis) we can do the same thing as above and construct a map that sends $F_*1$ to $1$ and the other generators to wherever we want. To check this use NAK! $F_*1$ is part of a minimal generating set if and only if $F_*1$ is non-zero in $F_*R/\mathfrak mF_*R$. By definition we can simplify $\mathfrak F_R= F_*\mathfrak m^{[p]}$, and clearly $F_1 \notin F_*\mathfrak m^{[p]}$. Thus we can extend to a minimal generating set (=free basis). ■

WARNING: It is NOT true that every regular local ring is $F$-split; we really do need some adjectives! We will see an example later in the semester.

Fedder's Criterion: Let $S$ be an $F$-finite regular local ring, and let $R=S/I$. Then $R$ is $F$-split if and only if $I^{[p]}:I\not\subseteq \mathfrak m^{[p]}$

It's stated there for motivation but it will take us a while to prove it. First we want to have a good understanding of what $\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ looks like, and how it relates to $\hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$. This will then help us figure out how a potential splitting of the Frobenius on $R$ might relate to one on $S$.

Remark: If $T$ is an $R$-algebra, then $\hom_R(T,R)$ has the structure of a $T$-module via premultiplication: $(t\cdot \varphi)(s) = \varphi(ts) $. So, $\hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$ has the structure of an $F_*^eR$-module via premultiplication: $(F_*^er \cdot \varphi)(F_*^es) = \varphi(F_*^e(rs))$.

Proposition: Let $k$ be an $F$-finite field, and let $S=$ either $k[x_1,\ldots, x_d]$, or the localization thereof at $\mathfrak m$, or $k[[x_1,\ldots, x_d]]$. Then $\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ is a free rank one $F_*^eS$-module. Specifically, if $\{F_*^e\lambda_i\}$ is a $k$-basis of $F_*^ek$ (where wlog $\lambda_1=1$), then $\Phi:F_*^eS\to S$ is our generator where $\Phi$ is defined on the monomial basis to be \[ \Phi(F_*^e(\lambda_ix^{\alpha})) = \begin{cases} 1 & i=1,\ \textrm{and }\alpha_j = (p^e-1)\ \forall j\\ 0 & \textrm{else} \end{cases} \]

Proof (when $k$ is perfect): $k$ is perfect means we don't have to worry about the $\lambda_i$ (a similar proof works with them there it is just more annoying to type out but not any more interesting). Let $\pi_\alpha$ be the dual (projection) to $x^{\alpha}$, so that \[ \pi_\alpha(F_*^e(x^{\beta})) = \begin{cases} 1 & \alpha = \beta\\ 0 & \textrm{else} \end{cases}. \]

- Goal 1: Show that each $\pi_\alpha$ can be written as $F_*^es\cdot \Phi$ for some $s\in S$. (Hint: First notice that $\Phi$ itself is a $\pi_\alpha$, and then see what $F_*^ex\cdot \Phi$ looks like in terms of the $\pi_\alpha$'s, and see if you can figure out a pattern.)

Let 𝟙 denote the all 1's vector. So $\Phi = \pi_{(p^e-1)𝟙}$, and more generally we HAVE a map that sends exactly one monomial to 1 (and the rest to 0), and we WANT maps that send exactly one monomial to 1 (and the rest to 0). So we should try acting by monomials. Specifically, \[F_*^e(x^{(p^e-1)𝟙-\alpha})\cdot \Phi (F_*^ex^{\beta}) = \Phi(F_*^e x^{(p^e -1)𝟙-\alpha+\beta}) = \begin{cases} 1 & (p^e-1)𝟙 - \alpha+\beta = (p^e-1) 𝟙 \\ 0 & \textrm{else}\end{cases}.\] I.e., it equals one exactly when $\beta = \alpha$. So $F_*^e(x^{p^e𝟙 -1 -\alpha})\cdot \Phi = \pi_\alpha$. ■

Observation: This shows why we needed $\Phi$ to send the LARGEST generator to zero. Otherwise the $x^{ (p^e-1)𝟙 -\alpha}$ we are acting by would have had the $(p^e-1)𝟙$ replaced by something smaller, and so the whole exponent would have been negative sometimes (bad because we're in a polynomial/power series ring).

- Goal 2: Show that the $\pi_\alpha$ generate $\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ as an $F_*^eS$ algebra.

Consider a map $\psi:F_*^eS\to S$. If we build a map that agrees with $\psi$ on the generators $x^\alpha$ then we're done. So define our candidate map \[\varphi= \sum_\alpha F_*^e(\psi(x^\alpha))^{p^e} \cdot \pi_\alpha \] which ensures \[\varphi(F_*^e(x^\beta)) = \sum_\alpha( F_*^e(\psi(x^\alpha)^{p^e}) \cdot \pi_\alpha)(F_*^ex^\beta) = \sum_\alpha \pi_\alpha(F_*^e(\psi(x^\alpha)^{p^e}x^\beta)) = \sum_\alpha \psi(x^\alpha)\pi_\alpha(F_*^ex^\beta) = \psi(x^\alpha)\pi_\alpha(F_*^ex^\alpha) = \psi(x^\alpha)\] as desired. Notice the magic that happened here---our action only allows us to act via pre-multiplication. However, by acting by a $p^e$-th power of an element, we get the same answer as if we acted by post-multiplication! In other words, the usual fact that the $\pi_\alpha$ generate as an $S$-basis (by typical dual basis fact) is also why we're getting that these generate over $F_*^eS$. ■

Now clearly combining Goal 1 and Goal 2 we see that $\Phi$ generates. For freeness, the only possible relation is of the form $F_*^es \cdot \Phi=0$. But this can never happen---$\Phi$ is non-zero on monomials of arbitrarily large degree! ■

Jan 29

Remark: In fact, $\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ is a free rank one $F_*^eS$ for any Gorenstein local ring $S$ (in particular, for any regular local ring). See Remark 5.9 of [CdS] for a proof. We'll use the regular case of this statement to be able to the following results for any regular local ring, not just polynomials/power series.

Proposition: Let $S$ be an $F$-finite regular local ring and let $\Phi$ be the generator of $\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$. Let $I$ and $J$ be ideals of $S$. Then \[ \Phi(F_*^eJ)\subset I \iff J\subset I^{[p^e]} \]

Proof: If $J\subset I^{[p^e]}$, then in fact for ANY map $\psi\in \hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ we have \[ \psi(F_*^eJ)\subset \psi(F_*^eI^{[p^e]}) \subset I\psi(F_*^eS)\subset I. \] For converse, first make several observations: By Kunz $F_*^eS$ is free over $S$, with basis $\{F_*^eg_i\}_{i=1}^t$. Let $\{\pi_i\}_{i=1}^t\subset \hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ be the dual basis (recall: this means $\pi_i(F_*^eg_j)=1$ if $i=j$, otherwise $0$). Further, because $\Phi$ generates, there exist $s_i\in S$ s.t. $\pi_i = F_*^es_i \cdot \Phi$. And \[\id_{F_*^eS} = \sum_i \gamma_i \circ \pi_i,\] where here $\gamma_i$ is the $S$-module map $S\to F_*^eS$ which sends $1\mapsto F_*^eg_i$. (Notice: this is the same as taking the $e$-th Frobenius map $S\to F_*^eS$, and then composing with multiplication by $F_*^eg_i$).

Now since $\Phi(F_*^eJ)\subseteq I$, we see \[\pi_i(F_*^eJ) = (F_*^es_i \cdot \Phi)(F_*^eJ) =\Phi(F_*^e(s_iJ))\subseteq I\] and so further, \[ F_*^eJ = \id_{F_*^eS}(F_*^eJ) = \sum_i \gamma_i \circ \pi_i(F_*^eJ) \subseteq \sum_i \gamma_i(I) = \sum_i I\gamma_i(S)\subseteq I \] as desired. ■

Theorem: Let $S$ be an $F$-finite ring, $I$ an ideal, and $R=S/I$. Then there is a natural $F_*^eS$-module map \[\Psi:(F_*^e(I^{[p^e]}:I))\cdot \hom_S(F_*^eS,S)\to \hom_R(F_*^eR,R).\] If $S$ is regular, then this map is a surjection and the kernel is $F_*^e(I^{[p^e]})\cdot \hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$.

Proof: The natural map: Let $t\in I^{[p^e]}:I$ and $\varphi\in \hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$. Given $r+I\in S/I=R$, we ideally want the resulting map on $\hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$ to have $F_*^e(r+I)\mapsto (F_*^et\cdot \varphi)(F_*^er) + I$. This will work! To check it is in $\hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$ we only need to check well-definedness, i.e., that things in $F_*^eI$ are sent to things in $I$. Sosuppose we have some $j\in I$. Then \[(F_*^et\cdot \varphi)(F_*^ej) = \varphi(F_*^e(jt))\in \varphi(F_*^e(I^{[p^e]}) = I\varphi(F_*^eS) \subset I.\] And by design, the overall map $\Psi$ is an $F_*^eS$-module map.

Surjectivity in the regular case: Since $S$ is regular we have $F_*^eS$ flat (by Kunz). Since $S$ also $F$-finite, we further have $F_*^eS$ a projective $S$-module. Thus ANY map $\theta\in \hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$ can be lifted to $\Theta\in\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ (using that the projection map $\rho:S\to R$ is surjective). By our knowledge of $\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$, we can write $\Theta = F_*^es \cdot \Phi$. To finish surjectivity, it will suffice to check that $s\in I^{[p^e]}:I$. But by virtue of the fact that $\Theta$ descends, \[I\supset \Theta(F_*^eI) = \Phi(F_*^e(sI)).\] Now by the Proposition above, $sI\subset I^{[p^e]}$, thus $s\in I^{[p^e]}:I$.

Kernel in the regular case: A map $F_*^et\cdot \varphi\in F_*^e(I^{[p^e]}:I)\cdot \hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ is in the kernel if it descends to the zero map, which happens exactly when $(F_*^et\cdot \varphi)(F_*^eS) = \varphi(F_*^e(tS))\subset I$. Now use the Proposition again, further writing $\varphi = F_*^es\cdot \Phi$, so that $\Phi(F_*^e(stS))\subset I$ and so $stS \subset I^{[p^e]}$. Thus $st\in I^{[p^e]}$, and we've shown that $F_*^et\cdot \varphi = F_*^e(st)\cdot \Phi$ is in $F_*^e(I^{[p^e]})\cdot \hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$ as desired. ■

The following theorem has been restated for clarity. (It was still true as stated in class though!)

Theorem: Let $S$ be an $F$-finite ring, $I$ an ideal, and $R=S/I$. Let $\mf q\in \bb V(I)\subset\Spec(S) $ be a prime ideal of $S$ that corresponds to a prime ideal in $R$. Then $R_{\mf q}$ is $F$-split if and only if (for any fixed $e$) \[(I^{[p^e]}:I)\not\subseteq \mf q^{[p^e]}.\]

Proof is promised for February 3rd!

Proof of Fedder's criterion ($I^{[p^e]}:I\not\subseteq \mf m$ version from Jan 27) using the above: Let $(R,\mf m)$ be our local ring. By the Lemma from Feb 3rd, $R$ is $F$-split if and only if $R_{\mf m}$ is $F$-split, i.e., $R$ is F-split at $\mf m$. By the above Theorem, this is if and only $(I^{[p]}:I)\not\subseteq \mf m^{[p]}$, as desired. ■

Feb 3rd

Today had a worksheet: [Fedder's Criterion]

Finishing the proof of the (more general) Fedder's criterion, including some necessary lemmas. Hopefully some examples. Also, set up an HCC account by Thursday if you want to follow along with the demo!

The following results will appear as exercises, in addition to a few more examples (squarefree monomial ideals?)

Lemma 1: If there exists a map $\pi:F_*^eR\to R$ such that $\pi(F_*^ed)=1$, and $c|d$ in $R$, then there exists a map sending $F_*^ec\mapsto 1$. In particular, if there is ANY surjective map $F_*^eR\to R$ then $R$ is $F$-split.

Write $d=cc'$, and let $\gamma':F_*^eR\to F_*^eR$ be the ``times $F_*^ec'$ map''. Then $\pi\circ \gamma'$ is our desired map, because it has $F_*^ec\mapsto F_*^e(cc')=F_*^ed \mapsto 1$.

The in particular follows since we can always choose $c=1$. ■

Lemma 2: Let $\ev_d:\hom_R(F_*^eR,R)\to R$ be the "evaluation at $F_*^ed$" map, so that $\ev_d(\varphi) = \varphi(F_*^ed)$. Then there exists a map $\pi\in \hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$ such that $\pi(F_*^ed)=1$ if and only if $\ev_d$ is surjective.

Since the codomain of $\ev_d$ is a free rank one $R$-module, being surjective is equivalent to having $1$ in the image. But this is then equivalent to saying there exists a $\pi$ such that $\ev_d(\pi)=\pi(F_*^e1)=1$. ■

Lemma 4: The following are equivalent for map $\varphi:M\to N$ of $R$-modules:

- $\varphi$ is surjective.

- $\varphi^{-1}R$ is surjective for all multiplicative sets $W$.

- $\varphi_{\mf p}$ is surjective for all prime ideals $\mf p$.

- $\varphi_{\mf m}$ is surjective for all maximal ideals $\mf m$.

Proof: A map is surjective iff its cokernel is zero, i.e., iff $N/\im(\varphi))=0$. And checking if a module is zero localizes! More specifically, for (1) equivalent to (2), we know that $\varphi$ is surjective iff $N/\im(\varphi)=0$ iff $W^{-1}(N/\im(\varphi))=0$ for all multiplicative $W$. Since localization exact, $W^{-1}(N/\im(\varphi)) \cong (W^{-1}N)/(W^{-1}\im(\varphi))$. Further, note that $W^{-1}\varphi$ (i.e., the map where $m/w\mapsto \varphi(m)/w$) has image = $W^{-1}\im(\varphi)$. Thus in fact $W^{-1}(N/\im(\varphi))\cong (W^{-1}N)/\im(W^{-1}\varphi)$, and this is zero iff $W^{-1}\varphi$ is surjective.

The arguments for (1) iff (3) and for (1) iff (4) follow similarly. ■

Proposition 1: The following are equivalent for any $F$-finite ring $R$:

- $R$ is $F$-split.

- $W^{-1}R$ is $F$-split for all multiplicative sets $W$.

- $R_{\mf p}$ is $F$-split for all prime ideals $\mf p$.

- $R_{\mf m}$ is $F$-split for all maximal ideals $\mf m$.

Standard comm alg result (Eloísa's 905 notes, Lemma 5.26): If modules are finitely generated, then localization commutes with Hom. In particular, \[\begin{aligned} W^{-1}\hom_R(F_*^eR,R) &\cong \hom_{W^{-1}R}(W^{-1}F_*^eR,W^{-1}R) \\ &\cong \hom_{W^{-1}R}(F_*^e(W^{-1}R),W^{-1}R). \end{aligned} \] By Lemma 2, $R$ is $F$-split iff $\ev_1$ is surjective. By Lemma 4, this is iff $W^{-1}\ev_1$ is surjective for all $W$. By the above standard result, $W^{-1}\ev_1$ can be viewed as a map $\hom_{W^{-1}R}(F_*^e(W^{-1}R),W^{-1}R)\to W^{-1}R$, and in fact by tracing through the isomorphisms this is $\ev_1$ for $W^{-1}R$. Thus by Lemma 2 in reverse, $W^{-1}\ev_1$ is surjective iff $W^{-1}R$ is $F$-split$.

That completes the proof of (1) iff (2). The proofs of(1) iff (3) and of (1) iff (4) work the same. ■

Corollary 1: If $R$ is $F$-finite then the locus of $F$-split points is open, and is specifically equal to $\Spec R \setminus \bb V(\im( \ev_1))$.

Rmk: The ``locus'' of $F$-split points is the set of points $\mf p$ on which $R$ is $F$-split. On Spec, points are prime ideals, and "being $F$-split at prime ideal $\mf p$ means that $R_{\mf p}$ is $F$-split. Finally, open means in the Zariski topology, where all open sets look like $U=\Spec R\setminus \bb V(J)$ for an ideal $J$.

The localization $R_{\mf p}$ is $F$-split if and only if $\ev_1$ localized at $\mf p$ is surjective, i.e., iff the cokernel $(R/\im(\ev_1))_{\mf p}$ is zero, i.e, iff $(\im(\ev_1))_{\mf p}=R$. That happens iff we inverted an element of the image, i.e., iff $\im(\ev_1)\not\subset \mf p$. By definition, this means $\mf p \notin \bb V(\im (\ev_1))$. ■

Lemma 3: Let $S$ be regular local $F$-finite, take $t\in I^{[p^e]}:I$ and let $\varphi=F_*^et\cdot \Phi$, where $\Phi$ is as usual the generator of $\hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$. Show that $\Psi(\varphi)$ (i.e., $\varphi$ viewed as a map on $S/I$) is surjective if and only if $t\notin \mf m^{[p^e]}$.

If $t\in \mf m^{[p^e]}$, then $\varphi(F_*^es) = \Phi(F_*^e(ts))\in \Phi(F_*^e(\mf m^{[p^e]})) = \mf m \Phi(F_*^eS) = \mf m$. In particular, we never hit $1$ in the image.

If $t\notin \mf m^{[p^e]}$, then our containment proposition from Jan 29 says $\Phi(F_*^e(tS))\not\subset\mf m$. Thus there is some $s\in S$ such that $\Phi(F_*^e(ts)) = \varphi(F_*^es) \notin \mf m$. Thus the image of $\varphi$ contains a unit, and so $\varphi$ is surjective. ■

Putting this all together... By the theorem on hom structure from Jan 29 (and by the fact that $I^{[p^e]}:I$ is an ideal), EVERY map in $\hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$ comes from a map of the form of Lemma 3. (See this because for any $t'\in I^{[p^e]}:I$ and $\gamma\in \hom_S(F_*^eS,S)$, we can write $\gamma = F_*^es \cdot \Phi$, and so $F_*^e(t')\cdot \gamma = F_*^e(t's)\cdot \Phi$.

By Lemma 1, there exists a $\varphi$ which is surjective when descended to $R$ iff $R$ is $F$-split. By Lemma 3, this happens iff there exists a $t\in I^{[p^e]}:I$ which is $\notin \mf m^{[p^e]}$. In other words, iff $I^{[p^e]}:I\not\subset \mf m^{[p^e]}$. This (FINALLY!) completes the proof of Fedder's criterion, and in fact in a stronger way where we see we could've done some/any $e$ instead of just $e=1$. ■

Feb 5th

Today had a handout: [Macaulay2 Cheatsheet]

Macaulay2 (M2) related links

- Web Macaulay2: https://www.unimelb-macaulay2.cloud.edu.au/

- The Macauly2 Documentation: https://macaulay2.com/doc/Macaulay2/share/doc/Macaulay2/Macaulay2Doc/html/

- The M2 Zulip chat (Zulip is a chatroom kinda like slack or discord; this can be a useful place to go with code questions): https://macaulay2.zulipchat.com/

- The M2 GitHub (not needed for most people, but could be useful if you want to install on your personal laptop, or if you want to file a bug report or contribute to code!): https://github.com/Macaulay2/M2

- Advanced users: You can pass command-line arguments to a .m2 file run as a script using scriptCommandLine and value in your M2 code.

Holland Computing Cluster (HCC) related links

- Swan Open OnDemand (aka, the way to access the HCC through a browser): https://swan-ood.unl.edu/ . You know you set up your account correctly if you are able to login at that link!

- HCC documentation: https://hcc.unl.edu/docs/

- Guide to basic shell (aka terminal aka console) commands: https://hcc.unl.edu/docs/connecting/basic_linux_commands

- VERY advanced users: You can pass in command line arguments to an sbatch command via the instructions in this stackexchange post.

Running M2 on HCC in interactive mode

To run Macaulay2 on the HCC in interactive mode... First go to Swan Open OnDemand. Click the dropdown menu for "Clusters" (in the red bar on top), then click the only option which is Swan Shell Access. You're now in a black background, text-only shell! Then run the following three commands one-by-one (commands themselves in the numbered list, comments/context bulleted in underneath each):

- srun --pty --mem=10gb --qos=short $SHELL

- Before running this line, the "prompt" (place I'm typing) looks something like [username@login1.swan ~]$

- This command might take a minute or two to run, with messages saying something about being queued, waiting for resources, and/or having resources allocated. Once it has completed, your new prompt will look something like [username@c0000.swan ~]$

- What's going on here? srun= "slurm run", i.e., running a "real time" job using SLURM (what SLURM is doesn't matter, but it does mean a lot of commands start with s...).pty= a specific interface format.mem= an amount of memory. I wouldn't ever go less than 10gb even for a "small" job because even just opening M2 can take some space!qos= "quality of service", aka how the system decides priority (if more people want to run code RIGHT NOW than the system can handle, who gets to go first?). So short means we'll get cut off after 6 hrs, and it might be sooner if tons of people are also requesting short jobs.

- Before running this line, the "prompt" (place I'm typing) looks something like

- module load apptainer

- By default installed programs aren't actually accessible to you, you need to "module load" them first. For example, "module load python". Here, "apptainer" is a way to get weirder and more niche programs.

- apptainer exec docker://unlhcc/macaulay2 M2

- This starts up M2, including "installing" it. The first time you do it, it might take a while (for me it took under 10 minutes, but more than 5). However, it will cache the result in something called a SIF file to make future loads faster! So if you ever see output messages about using cached SIF files, that's usually a good thing :)

TADA! After this you should now be in M2 interactive mode.

Uploading Files to HCC

Easy way:

- Go to Swan Open OnDemand.

- Click the dropdown menu for "Files" (in the red bar on top), then select "Work (math918)". Note: You can also use the "Home Directory" button, however, code run from Work will be faster!

- The page now shows a list of files (or maybe is empty if it's your first time). In the upper right, there are some white and blue buttons. Use the blue Upload button to upload a new file (for example, the demo files from below).Or use "New File" to create a new file from scratch (for example, to copy paste some M2 code from the web version).

From this screen you can also create/edit files! The New File button is near the upload button, and is useful for copy-pasting M2 code from the web version. To edit an existing file, scroll down to it in the list and click the meatball menu (3 vertical dots). Both of these (new file or edit) open a file editor. Be sure to save in the upper left when done!

Harder way: Use the scp (secure copy not slurm copy). From your laptops terminal, type

Submitting an asynchronous M2 job to the HCC (aka submitting a batch script)

The files from class: [Sample Batch Script] + [demo.m2]. Upload using instructions above!

To submit this, first need to get into the Swan Shell again. Login to Swan Open OnDemand. Click the dropdown menu for "Clusters" (in the red bar on top), then click the only option which is Swan Shell Access. You're now in a black background, text-only shell!

Now we need to find where the .submit file is. Here are several useful commands:

- lsLiSts what is in the current directory. (Do the files look like what you expected to see?)

- pwdPrints Working Directory, i.e., tells you the name of the folder you're currently in.

- cd /path/to/new/directoryChanges Directory to wherever you said. Useful special cases on the HCC are

cd /work/math918/username or cd $WORK to go to your work directory;

cd /home/math918/username or cd $HOME to go to your home directory;

cd .. (yes that's two periods no spaces in between them as the path to the file!) to go up one directory level.

Use that to get yourself to the directory with the .submit file. (If you followed the instructions under uploading, all you should need to do is cd $WORK but it is recommended to use ls to double check. Finally, run the following command:

where sbatch = "slurm batch", and you can replace helloworld.submit by any batch file.

Modifying helloworld.submit: To run an ACTUALY M2 file you care about, just change demo.m2 to the filename you actually want. For more advanced things, here's what's going on inside this file:

- Line 1 says "#!/bin/bash". Don't touch this!

- Look at the 2nd & 3rd lines, about runtime and memory. Do you need to request longer? Shorter? More memory? Less memory? If your job uses more time/space than requested the HCC will shut it down :( On the flip side, requesting execessive space/time will take it longer to get scheduled, and since the HCC is a shared resource, is rude.

- Line 4 is how the job name will appear in the queue. Only matters insofar as it is helpful to you, you can name every single job helloworld if you want.

- Lines 5 & 6 say where to put the output & any error messages. If the name starts with a number or letter (just plain helloworld.%J.err) then it will save the file in the same directory you're in when you run sbatch.

If the name starts with a slash (like /work/math918/abrosowsky/helloworld.%J.err) then it will put it in that specific folder, even if you're running sbatch from home instead of work.

If using the version from in class, DEFINITELY change abrosowsky to be your username otherwise you won't be able to access any of the output files. As of 02/09 evening I've changed the format so that my username no longer appears. - Replace demo.m2 in the last line of the file with the name of the m2 file you care about. Also, delete any echoes you want that's just for debugging demo purposes.

There are only two lines that actually matter (not counting the # ones):

module load apptainerapptainer exec docker://unlhcc/macaulay2 M2 --script demo.m2

Possible alternate method: The nice people at the HCC have made us a job template! In Swan Open OnDemand, click the dropdown menu for "Jobs" (in the red bar on top), then click "Job Composer". The macaulay2 template is called Apptainer-macaulay2-job. I still haven't figured out how to actually use the job composer but this might be helpful!

Troubleshooting

Error Messages? Take a look at the .err file. Does it give anything useful? My rule of thumb: totaly mysterious error usually = ran out of memory

Missing files? Did your output end up in home or in work? In a subfolder? Do you have two different HCC groups and put it in your advisor's group instead of the math918 group? Look through different options in the file browser, and double check in the batch file where you told it to save.

Other problem? Do you have another problem I should add to this list? Let me know!

Feb 10

F-splitting is nice, but can we do better? Our goal: describe a stronger condition on the ring that is still related to the Frobenius, but gets us even nicer properties.

Definition: Let $c\in R$. We say $R$ is $e$-$F$-split along $c$ if the map $R\to F_*^eR\to F_*^eR$ via $r\mapsto F_*^er^{p^e}\mapsto F_*^e(r^{p^e}c)$ splits as an $R$-module map.

Equivalently, there exists $\varphi\in \hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$ such that $\varphi(F_*^ec)=1$.

If there exists such an $e$, say that $R$ is eventually $F$-split along $c$.

Example:Let $R=\bb F_p[x]$, $c=x^p$.

- $R$ is NOT 1-F-split along $c$. Notice that for any possible $\varphi$, we have $\varphi(F_*x^p) = x\varphi(F_*1) \neq 1$.

- $R$ IS 2-F-split along $c$. In fact taking $\varphi = F_*(x^{p^2-p-1}\cdot \Phi$ works, where $\Phi$ is the generating map which sends $F_*x^{p^2-1}\mapsto 1$.

Remark 1: If $a|c$ and $R$ is $e$-$F$-split along $c$ then $R$ is $e$-$F$-split along $a$.

Proof: See Tuesday 02/03! Same statement just new vocab. ■

Corollary: If $R$ is $e$-F-split along anything, then $R$ is $F$-split.

Proof: If $R$ is $e$-F-split along $c$, then since $1|c$ we have that $R$ is $e$-F-split along 1. By definition this means there exists a $\varphi$ such that $\varphi(F_*^e1)=1$. ■

Remark 2: If $R$ is $e$-$F$-split along $c$ then $R$ is $(e+1)$-$F$-split along $c$.

Proof: Suppose $\varphi$ is our $e$-F-splitting. By the Corollary, we also know that $R$ is $F$-split, and so let $\pi\in \hom_R(F_*R,R)$ be our Frobenius splitting. Then $\pi\circ F_*\varphi$ is our desired map, since $$\pi\circ F_*\varphi (F_*^{e+1}c) = \pi(F_*\varphi(F_*^ec)) = \pi(F_*1) = 1 ■ $$

Proposition: If $R$ is eventually $F$-split along $c$ then $c$ is a non-zero divisor.

Proof Method 1: (contrapositive) Suppose $cy=0$ for $y\neq 0$. Then our map that we are trying to split sends $y\mapsto F_*^ey^{p^e}\mapsto F_*^e(y^{p^e}c) = F_*^e0$. So the map isn't injective and can't be split. ■

Proof Method 2: (contradiction) If we did have a splitting $\varphi$, we would have $$y = y\varphi(F_*^ec) = \varphi(F_*^e(y^{p^e}c)) = \varphi(F_*^e0) = 0$$ which is our desired contradiction. ■

Definition: Let $R$ be $F$-finite. Then $R$ is strongly $F$-regular (SFR for short on the board) if for all $c$ non-zero divisors, $R$ is eventually $F$-split along $c$.

Equivalently (1), $R$ is strongly $F$-regular if for all $c$ non-zero divisors, there exists an $e$ and $\varphi\in\hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$ such that $\varphi(F_*^ec)=1$.

Equivalently (2), $R$ is strongly $F$-regular if for all $c$ not in any minimal prime, $R$ is eventually $F$-split along $c$.

Proof that equiv (2) and original are the same definition: Recall that the set of zerodivisors is the union of all the elements in the associated primes, and that minimal primes are always associated. So if $R$ satisfies (2), then it automatically satisfies the original (since if you are a non-zero divisor you are DEFINITELY not in any minimal prime).

Conversely suppose that $R$ satisfies the original. Since 1 is a non-zero divisor, $R$ is eventually $F$-split along $1$, i.e., $R$ is plain old $F$-split. Thus $R$ is reduced, and reduced rings have no non-minimal associated primes. ■

Notation: $R^\circ = R\setminus \bigcup_{\mf p\in \Min(R)}\mf p$ is the notation for the set of elements not in any minimal prime.

Examples: (to be proved in a later class)

- $F$-finite regular rings are strongly $F$-regular

- $R=\bb F_p[x,y]/\langle xy\rangle$ is $F$-split, but not strongly $F$_regular

Theorem: Let $(R,\mf m)$ be a local $F$-finite strongly $F$-regular ring. Then $R$ is a domain.

We had some good discussions about $F$-finiteness, and I'm going to summarize it here: I'm following the convention of the books we're using, and making $F$-finite part of the definition of SFR. This means that saying it in the previous theorem statement is redundant! I'm going to do that a lot though for emphasis.

As Adam pointed out in the chat, the original definition of strong $F$-regularity did not require $F$-finiteness, and indeed there's nothing in the definition that needs it there. In particular while all of our references require this, it's not always required out in the wild. For more about F-singularities in the non-F-finite world, check out these notes by Takumi Murayama.

Fact: (we won't prove this) There exists a char $p$ ring $R$ which is regular, but such that $\hom_R(F_*R,R)=0$. In particular, this is a regular ring which is neither SFR nor even F-split.

Lemma 1: If $\bigcap_{i=1}^n\mf p_i\subset \mf q$ for prime ideals $\mf p_1,\ldots, \mf p_n, \mf q$, then there exists an $i$ such that $\mf p_i\subset \mf q$.

Proof: We only prove $n=2$, the rest is straightforward induction. If $\mf p_1\subset \mf q$, we're done. Otherwise there exists $a\in \mf p_1\setminus \mf q$. Observe that $\mf p_1\mf p_2\subset \mf p_1\cap \mf p_2$. For all $b\in \mf p_2$, $ab\in \mf q$ which by primeness means $b\in \mf q$ as desired. ■

Lemma 2: If $(R,\mf m)$ local and $f+g$ is a unit then either $f$ or $g$ is a unit.

Proof omitted

Lemma 3: $R$ is $e$-F-split along $c$ if and only if there exists $\varphi$ such that $\varphi(F_*^ec)=u$ a unit.

Proof: The forward implication is clear. For the backgwards implication, let $\psi = F_*^e(\frac{1}{u^{p^e}})\cdot \varphi$. Then $\psi(F_*^ec) = \varphi(F_*^e(\frac{c}{u^{p^e}})) = \frac{1}{u}\varphi(F_*^ec) = \frac{1}{u}u = 1$. ■

Proof of SFR + local implies domain: See proof of Lemma 3.2 in [MP]. ■

Theorem: Let $(R,\mf m,k)$ be a local $F$-finite regular ring. Then $R$ is strongly $F$-regular.

Proof: See proof of Theorem 3.4 in [MP] (ignoring the 1st line about reducing to the local case because we, by assumption, are already in the local case!) ■

Feb 12

We started with a return to Fedder's criterion.

- Let $k$ be an $F$-finite field and let $S=k[x_1,\ldots, x_d]$ be a polynomial ring. Let $I$ be a squarefree monomial ideal (so, $I=\langle m_1,\ldots, m_t\rangle$ where each $m_i$ is a monomial with no power $\gt 1$ on any variable). Prove that $S/I$ is F-split.

Let $g=(x_1\cdots x_d)^{p-1}$. Then $m_i^{p-1}|g$, and so $m_i^p|(m_ig)$, and so $g\in I^{[p]}:I$. But clearly $g\notin \mf m^{[p]}=\langle x_1^p,\ldots, x_d^p\rangle$, thus $S/I$ is F-split as desired.

- Let $k$ be an $F$-finite field and let $S=k[x,y,z]$. Let $f=x^3+y^3+z^3$. For which $p$ is $S/f$ F-split?

We know that $\langle f\rangle ^{[p]}:\langle f \rangle = \langle f^{p-1}\rangle$. Exapanding out, $$f^{p-1} = \sum_{a+b+c=p-1} \binom{p-1}{a,b,c} x^{3a}y^{3b}z^{3c}.$$ If one of these monomials is NOT in $\mf m^{[p]}$, we need $3a,3b,3c\lt p$, i.e., we need $a,b,c,\le \lfloor \frac{p-1}{3}\rfloor$. On the flip side, since $a+b+c=p-1$, this means we need $3\lfloor \frac{p-1}{3}\rfloor \geq p-1$, i.e., $\lfloor\frac{p-1}{3}\rfloor\geq \frac{p-1}{3}$. But a floor usually makes things smaller so this is only achieved when we have equality and $3|(p-1)$, i.e., when $p\equiv 1\mod 3$. Finally, note that the coefficient of $\binom{p-1}{a,b,c}$ is never $0$ mod $p$, since the numerator of $(p-1)!$ is never divisible by $p$.

Remark: A Stanley-Reisner ring is a polynomial ring mod a squarefree monomial ideal. Thus you have just proven that Stanley-Reisner rings are always $F$-split.

Facts: Let $I,J,J_1,J_2$ be ideals.

- $I:(J_1+J_2) = (I:J_1)\cap (I:J_2)$. In particular, $$I:\langle f_1,\ldots, f_t\rangle = \bigcap_{i=1}^t (I:\langle f_i\rangle.$$

- If $R$ is a domain, then $I:\langle f \rangle = \langle \frac{g_1}{f},\ldots, \frac{g_s}{f}\rangle$ where $I\cap \langle f \rangle = \langle g_1,\ldots, g_s\rangle$.

- If $I=\langle m_1,\ldots, m_t\rangle$ and $J=\langle n_1,\ldots, n_s\rangle$ are monomial ideals, then $$I\cap J = \langle \lcm(m_i,n_j)\: | \: 1\le i\le t,\ 1\le j \le s\rangle.$$ In particular, if $n$ is a monomial then $I:\langle n \rangle = \langle \frac{\lcm(m_1,n)}{n},\ldots, \frac{\lcm(m_t,n)}{n}\rangle$.

With those facts, we could compute $I^{[p]}:I$ in the Stanley-Reisner case if we wanted to... but it would be kind of annoying so our method is better! Check out the Wikipedia page on colon ideals for various other helpful properties of colon ideals.

Theorem: Let $R$ be an $F$-finite ring of prime char $p\gt 0$. Then $R$ is strongly $F$-regular if and only if $R_{\mf p}$ is strongly $F$-regular for all prime ideals $\mf p$.

Proof that SFR implies localizations are SFR: (Ref: Lemma 3.3 of [MP]) Suppose $R$ is strongly $F$-regular and let $\Min(R) = \{P_1,\ldots, P_n\}$, and let $\{P_t,\ldots, P_n\}$ be the primes of $R$ corresponding to the minimal primes of $R_{\mf p}$. Let $c\in R$ be such that $c/1 \in R_{\mf p}$ isn't contained in any minimal primes of $R_{\mf p}$. Then our goal is to show that $R_{\mf p}$ is eventually $F$-split along $c/1$.

Suppose that $c$ is contained in $P_1,\ldots, P_i$ but not in any other minimal primes of $R$. (Note that by definition of our choice, that $i\lt t$). Pick $c'\in \left(\bigcap_{j=i+1}^n P_j \right) \setminus \left(\bigcup_{j=1}^i P_i\right)$. Such a $c'$ exists by prime avoidance. Let $c'' = c+c'$, so that by design, $c''$ is not in any minimal prime of $R$. By SFR of $R$, there exists an $e\gt 0$ and $\varphi$ such that $\varphi(F_*^e c'')=1$. Then in $R_{\mf p}$ we get that $\varphi(F_*^e\frac{c}{1}) + \varphi(F_*^e\frac{c'}{1}) = \varphi(F_*\frac{c''}{1}) = 1$, and so either $\varphi(F_*^e(c/1))$ or $\varphi*(F_*^e(c'/1))$ is a unit.

But $c'/1$ is contained in all the minimal primes of $R_{\mf p}$, and so is a zerodivisor. Thus $\varphi(F_*^e\frac{c'}{1})$ can't be a unit, and so $\varphi(F_*^ec/1)$ is, as desired. ■

Feb 17

Proof that localizations SFR implies original ring SFR: (Ref: Lemma 3.3 of [MP]) Fix $c\in R^\circ$. For all $\mf p\in \Spec(R)$, we know there exists an $e$ (depending on $\mf p$) such that $R_{\mf p}$ is $e$-$F$-split along $c/1$. Since $\hom_{R_{\mf p}}(F_*^eR_{\mf p}, R_{\mf p}) \cong R_{\mf p}\otimes_R \hom_R(F_*^eR,R)$, this means that there exists a $\psi \in \hom_R*F_*^eR,R)$ and $f\notin \mf p$ such that $\varphi(F_*^ec) = f$. [Since this is exactly saying that $\varphi/f$ is our desired splitting in the localization.]

Let $\{f_\alpha\}_{\alpha\in \mc A}$ be the set of $f$'s appearing in this manner. Then $\bigcup_{\alpha\in \mc A} D(f) = \Spec(R)$. Further, $\Spec(R)$ is compact and so there exists a finite subcover so that $\Spec(R) = D(f_1)\cup\cdots \cup D(f_t)$. Let $e_i$ be the iterate corresponding to $f_i$, and let $e_0 = \max\{e_1,\ldots, e_t\}$. We've thus shown that $R_{\mf p}$ is $e_0$-$F$-split along $c/1$ for all $\mf p$. In other words, we've found a common $e$ that works for all primes!

Now, consider the evaluation maps discussed on Feb 3rd: $\ev_c^e:\hom_R(F_*^eR,R) \to R$ which sends $\varphi \mapsto \varphi(F_*^ec)$. Notice that $\frac{\ev_c^e}{1} = \ev_{c/1}^e \in \hom_{R_{\mf p}}(F_*^eR_{\mf p}, R_{\mf p})$. So now we know that $R$ is eventually $e_0$-$F$-split along $c$ if and only if $\ev_c^{e_0}$ is surjective if and only if $\frac{\ev_c^{e_0}}{1} = \ev_{c/1}^{e_0}$ is surjective for all primes $\mf p$, if and only if $R_{\mf p}$ is eventually $e_0$-$F$-split along $c/1$ for all primes $\mf p$. ■

Theorem: If $R$ is an $F$-finite regular ring then $R$ is strongly $F$-regular.

Proof: Regularity is a local property. By the previous result, SFR is a local property. So WLOG $R$ is local. But by the Theorem from Feb 10, a local $F$-finite regular ring is SFR. ■

Long-term Goal: Use SFR-ness to prove some results that, on the face of it, have nothing to do with the Frobenius! One such result will be that direct summands of regular rings are Cohen-Macaulay and normal. Another such result will be related to the next one:

Theorem: Let $R$ be $F$-finite and strongly $F$-regular. Then $R\hookrightarrow S$ splits for any module-finite extension $S$ of $R$.

To prove this, we broke the result down into several claims. We proved the first three in class, and the other claim + putting it all together to prove the theorem will be done on Thursday. (See Theorem 3.5 of [MP]).

Claim 1: If $R\hookrightarrow S$ is a module-finite extension, then $R\hookrightarrow S$ splits if and only if $R_{\mf p}\hookrightarrow (R\setminus \mf p)^{-1}S$ splits for all primes $\mf p\in \Spec(R)$.

This is very similar to the proof of F-splitting and SFR-ness localizing! Let $\ev:\hom_R(S,R)\to R$ be the "evaluation at 1" map, so $\varphi\mapsto \varphi(1)$. Then $R\to S$ splits if and only if $\ev$ is surjective. Since $S$ is module-finite, $R_{\mf p}\otimes_R \hom_R(S,R) \cong \hom_{R_{\mf p}}(S_{\mf p}, R_{\mf p})$, and $\ev/1$ is in fact evaluation at $1/1$ in $S_{\mf p}$. Since surjectivity localizes, we then have that $\ev$ is surjective if and only if the localizations $\ev/1$ are surjective for all primes $\mf p\in \Spec(R)$, which happens if and only if $R_{\mf p}\to S_{\mf p}$ splits for all primes $\mf p$. ■

Claim 2: Suppose that every module-finite extension $R'\hookrightarrow S'$ such that $R'$ is a SFR local domain and $S'$ is a domain splits. Prove that in fact EVERY module-finite extension $R\hookrightarrow S$ where $R$ is SFR splits.

In other words, prove that we can reduce the original theorem to the case where further $R,S$ are domains and $R$ is local.

By Claim 1, $R\hookrightarrow S$ splits if and only if $R_{\mf p}\hookrightarrow S_{\mf p}$ for all $\mf p$, thus WLOG we can assume that $R$ is local. By the Theorem from Feb 10, this automatically ensures that $R$ is a domain. Thus we've reduced to the case where $R$ is a local domain.

Now let $\mf q\in \Min(S)$, and consider the map $R\to S \to S/\mf q$. Clearly the composite $R\to S/\mf q$ is still module-finite, and by design $S/\mf q$ is a domain. Further, since $R\to S$ is integral, by lying over + incomparability, the minimal primes of $S$ lie over $\langle 0\rangle \in \Spec(R)$. In other words, $\mf q\cap R=(0)$ and so $R\to S/\mf q$ is injective.

Suppose that there exists $\pi:S/\mf q\to R$ a splitting. Then taking the composite $S\to S/\mf q \to R$ gives our desired splitting of $R\to S$. Thus we can use splittings where $S$ is a domain to build splittings for non-domains. ■

Claim 3: Let $R$ be a domain and $M$ be a finitely generated $R$-module. Prove that $M$ is torsion-free if and only if $M$ embeds into a finitely generated free module.

Since $R$ is a domain, any free module is torsion-free, and so any submodule of a free module is also torsion-free.

Now suppose that $M$ is torsion-free. Let $K=\operatorname{Frac}(R)$ be the field of fractions of $R$. Since $M$ is f.g., $M\otimes_R K$ is a finite dimensional $K$-vector space. Call the $K$-basis $e_1,\ldots, e_t$. Since $M$ is torsion-free, the map $M\to M\otimes_R K$ is an inclusion. Let $x_1,\ldots, x_n$ be a generating set for $M$. Viewing the images of these elements in $M\otimes_R K$, we can write in terms of our $K$-basis: \[\frac{x_1}{1} = \sum_{j} \frac{a_{ij}}{b_{ij}}e_j\] for $a_{ij},b_{ij}\in R$. Let $b=\prod_{i,j}b_{ij}$ be a common denominator. Then the image of $M$ in $M\otimes_K R$ is contained in $R\frac{e_1}{b} \oplus \cdots \oplus R\frac{e_t}{b}$, because clearly the generators of $M$ are all contained in this submodule. This is a finitely generated free module so we have proven our desired result. ■

Definition: $M$ is a solid $R$-module if $\hom_R(M,R)\neq 0$. $S$ is a solid $R$-algebra if $\hom_R(S,R)\neq 0$ (in other words, if $S$ is solid as an $R$-module).

Claim 4: Let $R$ be a domain and $M$ a finitely-generated $R$-module. If $M$ is a torsion-free $R$-module, then $M$ is solid.

We only need the above version but in fact something stronger is true:, When $R$ is a domain and $M$ is f.g., then $M$ is solid if and only $M$ is not torsion.

Proof: Next time!

Feb 19

Suppose that $M$ is a torsion-free $R$-module. Then $\iota:M\hookrightarrow R^{\oplus n}$ for some $n$, generated by $e_1,\ldots, e_n$. Let $x\in M$ be non-zero, and suppose that $x$ maps to $\sum_i a_i e_i$. Choose any $i$ such that $a_i\neq 0$. Then $\pi_i\circ \iota$, where $\pi_i$ is the projection onto $e_i$, is a map that sends $x\mapsto a_i$ and in particular is not the zero map.

For the stronger statement: if $M$ is not torsion, let $N$ be the torsion submodule so that $M/N$ is non-zero and torsion-free. By the above, we can find a non-zero map $M/N\to R$, and then we simply compose this with the natural quotient to get a non-zero map $M\to M/N\to R$.

Conversely if $M$ is torsion, then for all $x\in M$ there exists a non-zero $r\in R$ such that $rx=0$. For any $\varphi\in \hom_R(M,R)$ we must have \[0=\varphi(rx) = r\varphi(x).\] But $R$ is a domain, so this means $\varphi(x)=0$. ■

Claim 5: If $S$ is a solid $R$-algebra, then in fact there exists $\theta\in \hom_R(S,R)$ such that $\theta(1)\neq 0$.

Since $S$ is solid, there exists a non-zero $\varphi\in \hom_R(S,R)$. Choose some $s\in S$ such that $\varphi(s)\neq 0$, and sonsider the $R$-module map $\tau:S\to S$ via multiplication by $s$. We can then take $\theta = \varphi \circ \tau$, which has $1\mapsto s \mapsto \neq 0$. ■

Proof of Feb 17 Theorem: By Claim 2, WLOG $R$ is SFR local domain and $S$ is domain. Since $S$ is a domain it is a torsion-free $R$-module, so by Claim 4 it is a solid $R$-algebra and by Claim 5 there exists $\theta\in \hom_R(S,R)$ such that $\theta(1)=c\neq 0$. Since $R$ is SFR there exists $e$ and $\varphi$ such that $\varphi(F_*^ec)=1$. Then taking the map $\varphi \circ F_*^e\theta \circ F^e: S \to F_*^e S \to F_*^eR \to R$, we get that $1\mapsto F_*^e1 \mapsto F_*^ec \mapsto 1$. Thus this is our desired splitting of $R\hookrightarrow S$. ■

Definition: $R$ is a splinter if $R\hookrightarrow S$ splits for every module finite extension $S$ of $R$.

This lets us rephrase the theorem we just proved as

Theorem: If $R$ is $F$-finite and strongly $F$-regular then $R$ is a splinter.

Corollary: If $R$ is $F$-finite and regular then $R$ is a splinter.

To see how to remove the $F$-finite assumption, see the proof of Corollary 3.6 of [MP]. The more general statement that regular rings (in any characteristic!) are splinters is called the Direct Summand Conjecture, because it's equivalently saying that regular rings are direct summands of any module-finite extension. Although it's called the direct summand conjecture, this is actually now a theorem! In other words, a regular ring in ANY characteristic (including mixed) is a splinter, see André's paper "La conjecture du facteur direct".

Fact (Proved on HW3): Let $S=R_1\times R_2$. Then $S$ is strongly $F$-regular if and only if both $R_1$ and $R_2$ are strongly $F$-regular.

Proposition: Let $R$ be $F$-finite and strongly $F$-regular. Then $R$ is normal.

Let $\alpha\in \Frac(R)$ (our total ring of fractions) be integral over $R$. We want to show that in fact $\alpha\in R$. Write $\alpha = \frac{a}{b}$ for $b$ a nzd in $R$, and consider the map $R\to R[\alpha]$. This map is integral + algebra finite, therefore module finite. Since $R$ is a splinter, this map splits. Thus we have $\theta:R[\frac{a}{b}]\to R$ an $R$-linear map with $\theta(1)=1$. In particular, by $R$-linearity we have \[b\theta(\frac{a}{b}) = \theta(\frac{a}{1}) = a\theta(1) = a.\] Thus when viewed in $R[\frac{a}{b}]$ we see that $\theta(a/b) = a/b$. But also $\theta(a/b)\in R$. Thus $a/b=\alpha\in R$ as desired. ■

Corollary: If $R$ is an $F$-finite one dimensional strongly $F$-regular ring, then $R$ is regular.

Proof: One-dimensional normal rings are all regular. ■

Fact: If $S$ is a reduced normal ring, then $S=\prod_{i=1}^nS_i$ is a finite product of normal domains $S_i$. In particular, every strongly $F$-regular ring is a product of normal domains.

You will perhaps eventually see a proof of this in 906, but here is a reference (where we also recall that noetherian rings always have finitely many minimal primes, and that strongly $F$-regular rings are always reduced).

We didn't suceed at doing the whole proof. We got through explaining why we can reduce to the case where $R$ and $S$ are both domains. Next time we will start from the domain case.

Proof (that we can reduce to the domain case):

First, it suffices to prove that $R_{\mf p}$ is SFR for all primes $\mf p\in \Spec(R)$ (since SFR-ness localizes). Also, again by localization, we know that $(R\setminus \mf p)^{-1}S$ is SFR for all primes of $R$. (Technically for SFR we only talked about localization at primes. But notice that this implies similar results for an arbitrary multiplicative set by taking further localizations if necessary!) Finally, note that if the original map splits, so does any localization. Thus we can reduce to assuming that $R$ is local.

Second, note that $S$ SFR implies $S$ normal implies by Fact that $S\cong\prod S_1\times \cdots \times S_n$ is a product of normal domains. By Fact from HW3, these are in fact all SFR. Write this as $S \cong \prod_{i=1}^n S_i e_i$. Our final goal is to show that in fact, composition with one of the projections $R\to S \to S_i$ splits, so that we can replace $S$ by the domain $S_i$. And then since $R$ is a direct summand, that will force $R$ to be a domain as well (since it injects into a domain).

In order to show that one of these composites splits: Since $R\to S$ splits, let $\varphi$ be our splitting $S\to R$. Now we have \[1=\varphi(1) = \varphi(e_1+\cdots + e_n) = \varphi(e_1)+\cdots + \varphi(e_n)\] and since $R$ is local and this sums to a unit, there exists some $i$ such that $\varphi(e_i)$ is a unit. Now define a map $\phi:S_i\to R$ via $\phi(s_i) = \varphi(s_ie_i)$, in other words, $\phi = \varphi|_{S_i}$. This map is $R$-linear, and $\phi(1)=\varphi(e_i)=$ a unit. Thus by rescaling by the inverse of this unit, we get our desired splitting of $R\to S_i$. ■

Upcoming

Finishing up Ch 3 of [MP]: finishing the above proof that direct summands of SFR rings are SFR. Then we'll do the "test element" criterion (Thm 3.11 of [MP]) that reduces checking SFR-ness to checking eventual $F$-splitting along a single (well-chosen) $c$.